Data, Information and Knowledge

It is common to think at the current post-industrial global economy as an information-intensive environment. More remarkable is the high number of assertions that knowledge is the key of effective competition, marketplace distinction and profitability [1].

But which is the distinction between data, information and knowledge? The question can be answered in several different ways, here is one possible answer.

According to Davenport and Prusak [4] it is possible to define:

Data

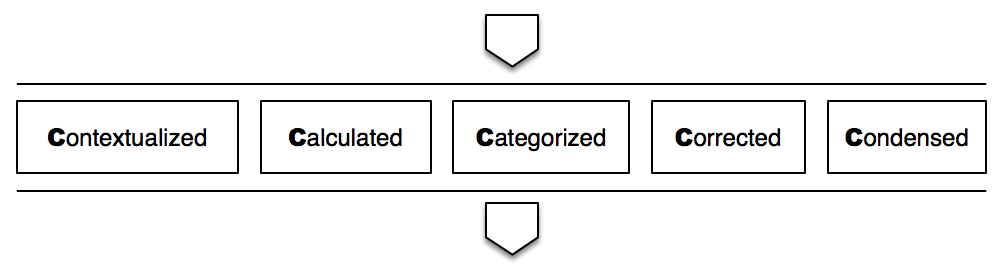

Is a set of discrete, objective facts about events. Data describes only a part of what happened; it provides no judgement or interpretation and no sustainable basis of action. But data is important to organizations because it is essential raw material for the creation of information. Data becomes information through the five "Cs":

Figure 1 - The transformation of data into information through the five "Cs".

Information

It has a meaning. It has a shape and it is organized to some purposes. "Information is data endowed with relevance and purpose. Converting data into information thus requires knowledge. And knowledge, by definition, is specialized" (Peter Drucker). Again information becomes knowledge through the four "Cs":

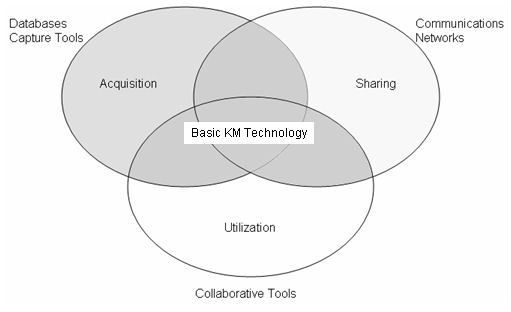

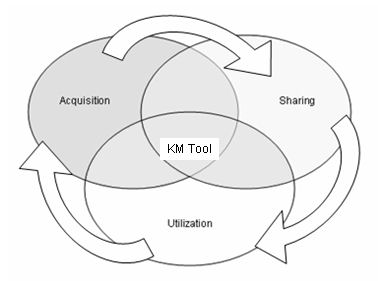

Figure 2 - The transformation of information into knowledge through the four "Cs".

Knowledge

Is a fluid mix of framed experience, values, contextual information, and expert insight that provides a framework for evaluating and incorporating new experiences and information. It originates and is applied in the mind of knowers. In organizations, it often becomes embedded not only in documents or repositories but also in organizational routines, processes, practices and norms.

Davenport and Prusak asserted that data become information when its creator adds meaning through different possible methods: contextualized (defined with a given purpose), categorized, calculated (mathematically or statistically), corrected and condensed (summarized). Computers and technology may foster the process but they hardly solve the problem of contexts, categories and summaries without human help. Humans carry out also the knowledge-creating activities directed to transform information into knowledge through different methods: comparison, consequences, connections and conversation.

The given knowledge definition is strictly connected to humans who are able to collect experiences, have belief, feelings, values and motivations. Knowledge is intuitive and exists within people, part and parcel of human complexity and unpredictability. Therefore knowledge is hard to capture in words or understand completely in logical terms [2]. The definition specifies also the function or purpose of knowledge: knowledge is a framework for "evaluating and incorporating new experiences and information". This is the basis for a process which continues along time.

This knowledge definition is in contrast with philosophical knowledge which is directed to discover the absolute truth (with the limit of the language that is not considered capable to express it) and with scientific knowledge which tends to discover general laws (through the experimental method). Demarest asserted that the goal of what he called "commercial knowledge" is not the truth in general, but effective performance: "what works" or even "what works better", where better is defined in competitive and financial contexts [1].

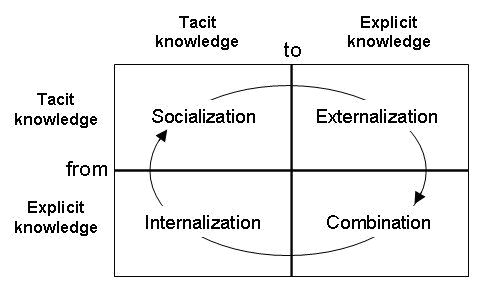

In the same way, knowledge as been defined by Nonaka and Takeuchi [5] as "justified true belief". Knowledge is provisional and partial, strictly dependent from the context that can rapidly change, it is not truth but appropriateness, capability of adaptation in a mutable and not completely defined environment.

Knowledge As Social Issue

Given the tacit/explicit conversion process, it is possible to assert that knowledge is social as produced and shared among a network of human and non-human actors within the organization. The mere existence of knowledge somewhere in the organization is of little benefit; it becomes useful only if it is accessible/sharable, and its value increases with the level of accessibility. This leads to the importance of communication/interaction (between humans and between humans and non-humans) as key factor for the success for a knowledge-intensive environment.